Architect

Alla Vronskaya, last edited on 15.06.2022

Name:

Natallya Maklaytsova (Bel: Наталля Мікалаеўна Макляцова / Rus: Наталья Николаевна Маклецова)

Life Dates:

1909-1993

Country:

Field of expertise:

Architectural design

Education:

Leningrad Institute of Engineering and Construction

Born in Smolensk region in the west of Russia in 1909, Maklaytsova lost her mother, a student at Higher Women Polytechnic Courses in St. Petersburg, in 1913; shortly after, her father, a graduate of the Institute of Civil Engineers in St. Petersburg, was drafted to the army during the First World War–never returning home, he immigrated to Canada in the 1920s. Maklaytsova was raised by her grandmother and was able to study architecture at Leningrad Institute of Engineering and Construction, from which she graduated in 1931. Upon graduation, she moved to Minsk, where a regional branch of Ginprogor (Bel. Dzipragar) institute was being created at that time. In 1933, the Dzipragar Minsk branch was reorganized as Beldzyarzhpraekt. In addition to her work at the institute, Maklaytsova taught design at Minsk College of Architecture and Construction and descriptive geometry at the Minsk Institute of Construction.

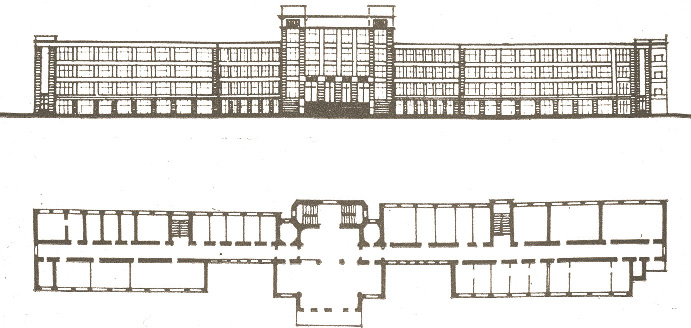

The rapidly growing city presented multiple opportunities for an architect, and Maklaytsova’s first major building, a 100-apartment residential building for the technical elites, was erected in 1934; in 1938, she became the architect of the main building of Belarusian Polytechnic Institute. In the 1930s, Maklaytsova enrolled into the doctoral program of the Academy of Architecture in Moscow and was a delegate to the First Congress of Soviet Architects in 1937, a milestone event attended by Frank Lloyd Wright.

In April 1941, Maslaytsova was asked to move to the Voenproekt (Military Design) office, which was tasked with building military infrastructure, but this work was shortly after interrupted by the invasion of the German army. Eighty percent of the existing city, including all but one Maklaytsova’s projects, was destroyed by bombings during the first days of the war. During the war, she remained in occupied Minsk with her daughter (born in 1932). At this time, she met her second husband, construction engineer Vladimir Minkevich, who would become the head engineer of DSK-1, the first factory of panel residential construction in Belarus. Their son was born in 1942. At this time, Maklaytsova worked at a private construction company, founded by her former student under the German occupation, and designed a tobacco factory.

After the retreat of the German army Maklaytsova began teaching at the newly-reopened Belarusian Polytechnic Institute, while also working at Beltraktorstroy (Belarusian Tractor Construction) trust, created to support the construction of Minsk Tractor Factory, and in Belprampraekt, where she was the chief architect in 1944-1948. In 1952, Maklaytsova defended her doctoral dissertation, devoted to residential architecture in Belarus, and moved to full-time teaching at Belarus Polytechnic Institute. She became the first woman teaching architecture in Minsk. The only surviving building by Maklaytsova remains the 1935 building currently occupied by Minsk State Polytechnic College.

At school, they conducted an experiment: they offered us test questions and, based on our answers, socio-psychologists gave us recommendations to each of us as to whether to continue education in a technical field or in humanities. I was given “green light” to go either way. Maybe because of this, or maybe because my father had studied there, I chose the Institute of Civil Engineers, later LISI [Leningrad Institute of Engineering and Construction].

…My last year at the institute, the fourth year, early spring graduation. On April 1st we graduated the institute, passed the last tests and term papers… It was strange to receive diplomas, which gave us the title of “Architect Engineer”.

There was nothing for me to do in Leningrad, there was no place to live… so the “great” decision was made – to move to a new place, to new people. In Minsk, a branch of Giprogor was being created. There were two places for architects and I applied for a position, got the start-up help

and went to Minsk. I thought I am going there for a couple of years, but I was stuck there for the rest of my life, and in general, I don’t regret it.

So, the Minsk era (1931 to the end of days).

On September 25, 1931 I found myself in the station square of the capital of Belarus and was upset. I remember that moment very well, as if it was yesterday. One-storey railway station building, the square paved in cobblestones, coachmen with shabby carriages and the pouring rain. Directly opposite the station’s entrance, a short street, now Kirov Street. Instead of the present-day monumental towers, on both sides of the street are stumpy wooden one-storey houses, all rather pathetic after the vastness and beauty of Leningrad.

…

There were only six architects in Minsk at the time, and here was a new architect – and it was a woman! I was immediately offered to supervise diploma projects at the College of Architecture and Construction and to teach descriptive geometry in the second year of the of the Construction Institute, both conveniently located near the People’s Commissariat.

…

The city’s population was growing by leaps and bounds, and there was a catastrophic shortage of housing. It was urgent to design and build, build, build. There was enough work for everyone, life was interesting, although we received food by ration cards, and the wages were minimal. But this did not affect our ability to work: on the contrary, we worked with enthusiasm, spending long evenings in the office. If necessary, we even worked nights and did not ask for time off. Such were the times and the people. Already in 1934, the construction of a 100-apartment House of Specialists began after my project. It was an event in construction practice. The first house with a six-storey (!) middle section, with elevators and a basement.

Nowadays such houses are built in tens of dozens each year, but at that time it took more than two years to build it, and three- and four-room apartments were allocated to several families each, one family per room.

Alas, my first architectural creation perished on June 24, 1941. On that horrible day the entire city was killed. Eighty percent of buildings were destroyed by bombing and fires.

During those (pre-war) years many interesting and memorable events took place in my life.

A competition project for the Opera House, the creation of the Union of Architects of Belarus. A trip to Moscow to take professional development courses, enrollment into the doctoral program of the Academy of Architecture… In 1937, the First Congress of Soviet Architects took place and I was elected a delegate. Unforgettable days in Moscow. A kaleidoscope of people, among whom were old friends from the institute, new acquaintances, and architectural celebrities of those years; our country’s celebrities and foreign guests. Even Frank Lloyd Wright, the patriarch of American architecture, gave a speech. A luxurious banquet for all the delegates was organized by the Moscow City Council in the building of the not yet opened Khimki River Port. At 4 in the morning we boarded comfortable steamships for a wonderful trip on the new Moscow – Volga canal.

…In early April of 1941 I, together with many other specialists, was invited to the Communist Party Central Committee and was offered to go to work at the military design office. In short, I was mobilized because it was necessary to urgently design defense facilities in Western Belarus: airfields, fuel and lubricants depots and military supplies, military camps. We worked seven days a week, twelve hours a day. Everything was urgent and top-secret. It was sad and upsetting when on June 25 we had to burn all of these efforts, which had been saved from the fire [caused by bombing the day before], before retreating from the blazing city. There was no one left to evacuate the blueprints and there was no one left to evacuate the blueprints and the calculations.

…

In the morning [of 22 June], as usual, I went to work. The city seemed to stand still, only in the middle of the day there were a few distant explosions and high-flying planes. It turned out that the Germans had bombed the Elvod, the city was deprived of water and light. As it later turned out, several special trains left Minsk late at night. The government and other governing bodies had left with their families. We were given the command to go to work, no matter what. And we were still going to work on the 25th, when we burned our works.

…June 24, the third day of the war. At about 12 o’clock a terrible bombing began. The planes

with black crosses on their wings. …flew in swarms and bombed the city… square by square. Incendiary and high-explosive bombs were falling side by side. …The city was burning, the bombs kept falling, not a single our aircraft rose into the air…

On the night of June 26, we spent the night in Chelyuskintsy Park; it was scary to stay in the city. Early in the morning, we went east along the Moscow highway in a crowd of frightened refugees. I can still see that gruesome picture: disheveled, smeared faces of women with children in their arms. An old man clutching a Viennese chair to his chest, a gray-haired woman carrying pots, people holding the keys of burnt apartments in their hands… The scorching sun, the dust, the bitter smoke of the solid conflagration, in which our Minsk perished on the fourth day of the war…

The Germans entered Minsk on June 27. When we returned on July 7, the front yard of the Polytechnic, which had burned down on June 24, was surrounded by barbed wire, and a huge camp of war prisoners had already been set up there. There were many such camps

near Minsk…

…

The settlement of MTZ [Minsk Tractor Plant] was just beginning to be built up. The bulk of the inhabitants were housed in panel barracks. A school was opened in one of them. In the ravine behind the barracks, temporary buildings grew up like mushrooms. Individual construction began. The builders were the settling Roma and displaced peasants, whose village were destroyed by the Nazis.

Just before the war a construction of an aircraft plant began on the site of present-day MTZ. They managed to make basements under the workshops and the embankment for the tramway. Here, in 1946 a grandiose construction unfolded. The main workforce were German prisoners of war whose camp was located in those basements.

…

In January 1945 the Belarusian Polytechnic Institute reopened. The pre-war students, who did not finish their courses, were admitted to the Institute. There were 10 to 12 students in a cohort at that time. The faculty members were coming back. I was summoned to the rector and offered part-time work in addition to my existing position, which I gladly accepted. The classes were held in different parts of the city: in the hall of the Institute of Physical Education, in the basement of the Trade Unions on the Freedom Square, in school No.13 on Ya Kolas street. It was very cold there. We were studying in coats, overcoats, and mittens. The students lived in the reconstructed building on the university campus, which had a roof, ceilings, and glazed windows, and the bedrooms stretched the entire floor from staircase to staircase. There were 200 people in one room. But all of that was unimportant compared to what we had experienced during the war. Everyone had a tremendous desire to teach and study.

Source:

The archival collection of Natallya Maklyatsova at Belarusian State Archive of Scientific-Technical Documentation: https://fk.archives.gov.by/fond/110358/

Xenia Khachatryants, “Natalya Nikolaevna Makletsova. Iz vospominaniy” [Excerpts from Natallya Maklyatsova’s memoir, in Russian] Arkhitektura i stroitelstvo, No. 2, 2004: 29-33. Available online: https://ais.by/story/211

Olga Sakharova, “Pervaya zhenshchina-arkhitektor Minska: Ona voevala za vosstanovlenie stolitsy,” Minsk News, 9.05.2020: https://minsknews.by/pervaya-zhenshhina-arhitektor-minska-ona-voevala-za-vosstanovlenie-stoliczy/

“Kak zhila i chto sozdavala v stolitse pervaya zhenshchina-arkhitektor Natalya Makletsova.” Video by CTVBY (in Russian): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J3wlUUl1QzY

https://www.wiki.be-by.nina.az/Наталля_Макляцова.html (last accessed on 20.04.2022)

Fig. 4: https://pervadmin.gov.by/zdanie-pr.-nezavisimosti,-85#gallery (last accessed on 20.04.2022)

Fig. 5: https://minsknews.by/pervaya-zhenshhina-arhitektor-minska-ona-voevala-za-vosstanovlenie-stoliczy/ (last accessed on 20.04.2022)

We assume that all images used here are in public domain. If we mistakenly use an image under copyright then please contact us at info@womenbuildingsocialism.org or here.